From Studio B-2 at the BBC headquarters in London, General Charles de Gaulle prepared to address his countrymen in German occupied France. He had fled Paris by plane only hours prior, narrowly escaping the battalions of the advancing German army. While de Gaulle’s plane crossed the British Channel, Marshal Henri Petain, hero of WWI and mentor to the newly promoted General de Gaulle, replaced Paul Reynaud as the Prime Minister of France. His first act as head of state was to announce his plan to sign an armistice with Germany. The invasion had lasted a mere thirty-five days. France was outraged. Defeated, humiliated and betrayed, the French were hopeless.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met de Gaulle’s plane on the tarmac. There, Churchill urged the General to broadcast a message to the people of France. Churchill hoped that de Gaulle could encourage the French during one of their darkest days and inspire the people to continue the fight against the Nazi war machine.

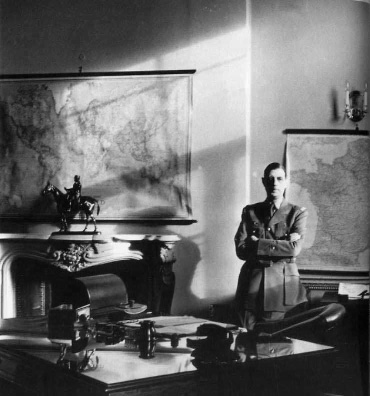

General de Gaulle was no major figure, in fact he was practically unknown in France. However, for the past several weeks, he had been furiously urging his government to continue the fight against Germany. With the ascension of the Vichy government, de Gaulle was sure his arrest would soon be ordered. A public-address denouncing the armistice would make his status as a traitor and an international fugitive a certainty. Despite the danger to himself and his family, de Gaulle could not, and would not, sit idle as his government turned its back on its people and their heritage. He was committed to continuing the fight no matter the cost. And, at 6 p.m. on June 18th, 1940 General Charles de Gaulle abandoned his beloved France, for the sake of the French people.

De Gaulle’s Speech

The leaders who, for many years, have been at the head of the French armies have formed a government. This government, alleging the defeat of our armies, has made contact with the enemy in order to stop the fighting. It is true, we were, we are, overwhelmed by the mechanical, ground and air forces of the enemy. Infinitely more than their number, it is the tanks, the aero-planes, the tactics of the Germans which are causing us to retreat. It was the tanks, the aero-planes, the tactics of the Germans that surprised our leaders to the point of bringing them to where they are today.

But has the last word been said? Must hope disappear? Is defeat final? No!

Believe me, I who am speaking to you with full knowledge of the facts, and who tell you that nothing is lost for France. The same means that overcame us can bring us victory one day. For France is not alone! She is not alone! She is not alone! She has a vast Empire behind her. She can align with the British Empire that holds the sea and continues the fight. She can, like England, use without limit the immense industry of the United States.

This war is not limited to the unfortunate territory of our country. This war is not over as a result of the Battle of France. This war is a world war. All the mistakes, all the delays, all the suffering, do not alter the fact that there are, in the world, all the means necessary to crush our enemies one day. Vanquished today by mechanical force, in the future we will be able to overcome by a superior mechanical force. The fate of the world depends on it.

I, General de Gaulle, currently in London, invite the officers and the French soldiers who are located in British territory or who might end up here, with their weapons or without their weapons, I invite the engineers and the specialized workers of the armament industries who are located in British territory or who might end up here, to put themselves in contact with me.

Whatever happens, the flame of the French resistance must not be extinguished and will not be extinguished. Tomorrow, as today, I will speak on the radio from London.

At the conclusion of his first broadcast, de Gaulle had begun a transformation from a soldier in service to his country, to the self-proclaimed leader of the Free French and the very embodiment of France itself.

In his memoirs de Gaulle wrote that, “As the irrevocable words flew out upon their way, I felt within myself a life coming to an end—the life I had lived within the framework of a solid France and an indivisible army. At the age of forty-nine I was entering upon adventure, like a man thrown by fate outside all terms of reference.”

One author writes that, de Gaulle seemed to have stepped “straight out of the pages of history, a ‘reincarnation of the Capetian kings’” who was determined “to bring unity to France in order to make it the equal in spirit of the ‘colossus’ of the past, to restore its grandeur and sense of responsibility.”

For now, however, de Gaulle had taken his first steps to reclaim France for the French.

Part One

Early Life

Charles de Gaulle was born on November 22, 1890 to an intensely Catholic and conservative family with deep French roots. His father, Henri de Gaulle was a veteran of the Franco-Prussian War. After a humiliating defeat by Prussia, which later became Germany, Henri de Gaulle, returned to France and became a teacher of philosophy and mathematics. France’s loss in the war forever colored the life of de Gaulle’s father, a patriot who vowed he would live to avenge the defeat and win back the lost provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. He groomed his sons in this patriotic obsession to restore France to the pinnacle of European power.

His mother, Jeanne Maillot de Gaulle, assisted her husband by immersing their children in the de Gaulle family’s heroic role in the history of France. As early as the fourteenth century, the de Gaulle family had been serving their homeland when one Chevalier de Gaulle fought back an invading English army at the city of Vire. An ancestor of de Gaulle’s is even cited as being present at the great Battle of Agincourt in 1415. Charles de Gaulle’s great-great-grandfather was a king’s counselor and his grandfather Julien Phillippe de Gaulle wrote a popular history of Paris.

Through the history of their bloodline the de Gaulle’s instilled in their children an anxious concern about the fate of France. In his War Memoirs, Charles de Gaulle writes that, “[a]s an adolescent, the fate of France, whether as a subject of history or the stake in public life, interested me above everything.”

Early Career

This great concern for France led de Gaulle to pursue a career in the military and in 1910, he applied to the Saint-Cryr officer academy in Guer, France. There his insatiable devotion to country and his haughty attitude earned him nicknames such as “The Grand Constable”, “The Fighting Cock”, and my personal favorite, “The Big Asparagus.”

After receiving his commission 1912, de Gaulle asked to be returned to the 33rd Infantry where he had spent a year before his education. In the 33rd, Second-Lieutenant de Gaulle fought in World War I under the command of Colonel Henri Pétain. Two battlefield injuries did not deter the young de Gaulle who returned to the 33rd just in time to take part in the fateful Battle of Verdun.

On March 2, 1916, Captain de Gaulle’s frontline company was in position at Douaumont, a key fortified height near the center of Verdun. The next day the company’s position was overrun by the Germans. De Gaulle, unwilling to admit defeat, rallied his troops and fought through the enemy trenches attempting to re-connect to France’s main defensive line.

Fort Douaumont

During the surge, de Gaulle was shell shocked by a grenade blast. Before he could recover, he was stabbed by a German bayonet. The wound slowed the assault but did little to diminish his resolve. However, despite his efforts, the German resistance was to strong and de Gaulle’s rally ended when he succumbed to the effects of poison gas. De Gaulle was left for dead on the battlefield of Verdun.

Eventually, he was picked up when the Germans came to collect the bodies for burial. De Gaulle, however, had only been knocked out by the gas and came to while piled on a Graveyard Cart with the other corpses. When the Germans realized that he was still living, he was sent to a POW camp, where after five un-successful escapes he was transferred to a maximum-security prison-fortress for the remainder of the war. On December 1st, 1918, three weeks after the armistice ending WWI, de Gaulle returned to his father’s house in France where he was re-united with his three brothers—all had served in the war.

Between the Wars

In 1919, Captain de Gaulle joined the staff of the French Military Mission to Poland. There, he distinguished himself in operations near the River Zbrucz, earning him the rank of major in the Polish army, and winning Poland’s highest military decoration, the Virtuti Militari. When de Gaulle returned to France, he became a lecturer in military history at Saint-Cryr.

In 1922, de Gaulle continued his military education with two years of special training in strategy and tactics at the staff college in Guerre. There, de Gaulle often clashed with his instructors over the traditional tactics favored by the French military. In WWI, de Gaulle had witnessed the failure traditional strategies, such as static defensive lines, against the mechanization of warfare. Instead, he argued for implementing tactics that focused on flexibility and speed. This disagreement frequently erupted into conflict with his instructors who viewed de Gaulle as egotistical, haughty and stubborn.

This antagonism nearly torpedoed his career. Fortunately, he was saved through the intersession of his old commander Pétain who arranged for de Gaulle to be transferred to the headquarters of the French Army of the Rhine in Mainz.

By 1931, he had spent two years on assignment in Trier, two years in Beirut, received a promotion to commandant, and finally was promoted to the General Secretariat of the Supreme Council of National Defense based in Paris. There, de Gaulle got his first experience in the interface between army planning and government. In this role, de Gaulle began to argue for drastic military reforms in the French army. He was highly critical of reliance on static defenses like the Maginot Line—France’s $550 million dollar network of bunkers, trenches, and gun implements stretching for 280 miles along the German border. Instead, he continued to argue for flexible tactics aimed at mobility and speed. He believed that tanks, high caliber artillery, and other mechanized weaponry would comprise the military of the future.

In 1934, de Gaulle published Toward a Professional Army in which he proposed mechanization of the infantry. Though rejected by the military elite, de Gaulle’s ideas attracted the attention of the maverick politician Paul Reynaud who also believed that mechanized warfare had made static defenses like the Maginot Line obsolete. De Gaulle’s persistent lobbying for mechanization earned him command of the 507th Tank Regiment as well as a new nickname, Colonel Motors.

Part Two

The Battle of France

Despite the warnings of de Gaulle, the French were confident in the ability of the Maginot Line to deflect any conventional means of attack. However, when the Nazi invasion began in May of 1940, their strategy was anything but conventional. To counter this new threat, de Gaulle was given control of the 4th Armored Division which was intended to boast over five hundred tanks, mobile artillery and light armored vehicles. However, when de Gaulle took command, only three tank battalions were ready for deployment.

On May 12th, de Gaulle was ordered to launch a counter-offensive in order to give the Sixth Army time to redeploy from the Maginot Line. The next day, German forces shattered the Allied defensive strategy by circumventing the Maginot Line through the heavily wooded French Ardennes. On the 17th, de Gaulle counter-attacked at Mountcornet, an important strategic crossroads in Northern France. After two days of intense fighting, de Gaulle was ordered to withdraw. Though outnumbered and without air-support, de Gaulle ignored the order and by the 19th, the 4th Armored Division forced the German infantry to retreat to Caumont.

Mountcornet was one of the few Allied successes of the Battle of France. In recognition for his efforts, de Gaulle was promoted to brigadier-general.

By May 20th, the German spearhead had advanced to the French coast, cutting off British, French and Belgian forces from the main body of the French Army. With the complete annihilation of the allied armies in his grasp Adolf Hitler inexplicably ordered Army Groups A and B to halt their advance. This three-day reprieve allowed the Allies to organize in escape route across the British Channel. A final counter-offensive was launched by Allied forces on May 28th. The attack was designed hold back the German advance as Allied troops stranded at Dunkirk were evacuated to the British Isles. De Gaulle’s 4th Armored Division attacked the German bridgehead south of the Somme at Abbeville. The attack succeeded in holding the German advance at bay and by June 4th, over 330,000 Allied troops had safely crossed the British channel. The next day, de Gaulle was appointed Under-Secretary of State for National Defence and War by Prime Minister Reynaud and recalled to Paris.

Over the next two weeks, defeatism swept the French government. While the old guard began to seek an armistice, de Gaulle and Reynaud desperately argued for evacuating the government to French North Africa. Despite their efforts to continue the fight, Paris was declared an open city on June 10th. Four days later, de Gaulle was sent to London by Reynaud to discuss a potential evacuation to French North Africa with the English.

He returned to the temporary headquarters of the French government in Bordeaux on June 16th, around 10 p.m. There, he was informed that he was relieved from his post as Under-Secretary and that Prime Minister Reynaud had resigned. Eleven hours later, de Gaulle, narrowly evading capture by French authorities, commandeered an airplane and escaped to London with $100,000 gold francs in secret funds which had been given to him by Reynaud. When the plane landed in London at 12:30 p.m. on June 17th, de Gaulle was an exile and a fugitive in a foreign country.

World War Two: Forging the Free French

Following his proclamation on the BBC, de Gaulle struggled incessantly to rally his Fighting French. During the critical period from 1940-1942, the fate of Free France hung in a precarious balance between the small, slow trickle of victories that held it together, and the ever-present specter of political suicide. Both were the result of de Gaulle’s own “intransigence” as he often termed his haughty, yet effective political tactics. Edward Spears recalls, “In those days de Gaulle had very few cards and no trumps. He realized his only chance was to play an aggressive game, overcall his hand, bang the table, and he did so.”

Much of de Gaulle’s so called “intransigence” can be properly attributed to necessity. He was a lone voice competing amongst vast interests. De Gaulle, speaking about his relationship with Churchill, once stated that, “When I am right, I get angry. Churchill gets angry when he is wrong. We are angry at each other much of the time.” On more than one occasions the Frenchman pushed Churchill’s patients to the limit. In 1941, de Gaulle told Churchill that the French people thought he was a reincarnation of Joan of Arc, to which Churchill replied that the English had had to burn the last one.

Despite their tense relationship, the Free French movement depended almost exclusively on the charity of the English and Churchill in particular. The American government, on the other hand, had no interest de Gaulle, who Roosevelt referred to as “an apprentice dictator.” De Gaulle’s own intransigence did nothing to improve these relations. Instead, the Americans began pursuing contacts in the Vichy government in the hopes that one would blossom into a resistance movement.

A secretary, a few military officers, and an office suite at 4 Carlton Gardens in London was the extant of the resources with which de Gaulle had to rebuild France. The New Hebrides, a small island chain near Australia, were the only French colony to back de Gaulle. Two weeks after his proclamation on the BBC, de Gaulle’s military forces were bolstered when he was joined by the French Admiral Muselier. In August, de Gaulle was able to reach an agreement with Churchill that Britain would fund the Free French, with the bill to be settled after the war.

With few followers, sparse funds and little influence in global affairs, de Gaulle’s cause seemed nearly hopeless. The Vichy, on the other hand, controlled the French fleet and the forces in almost all her colonies, and was recognized by the United States and Russia as the official government of France.

In spite of this desperate position, de Gaulle continued encourage the people of France over the BBC at least three times a month. These speeches were heard throughout France where they helped to rally the resistance movement. In his addresses, de Gaulle encouraged the French resistance fighters to build a network of propagandists, spies and saboteurs to harass the German occupiers. Jean Moulin, a prominent French resistance fighter, was tasked by de Gaulle with organizing the various resistance movements throughout France into a cohesive guerilla force. Eventually, Moulin gathered the leaders of the disjointed groups into one organization, the National Council of Resistance (CNR). The CNR became de Gaulle’s formal link to the Resistance in France.

De Gaulle and the French Resistance won a major victory with the Allied invasion of Algiers in November 1942. In the early morning hours on the day of the Allied invasion, four hundred French Resistance fighters staged a coup in the city of Algiers. By the time the landing began, all of the coastal batteries had been neutralized allowing the Allies to quickly gain a beachhead. De Gaulle moved the headquarters of the Free French to Algiers in May of 1943.

In 1943, the American government succeeded in convincing General Henri Giraud to join the cause of the Allies. However, Giraud’s close ties to the Vichy government and his less than able political skills caused an uproar in America and Britain. With this in mind, Roosevelt decided to invite both Giraud and de Gaulle to an Allied conference on the island of Casablanca.

Roosevelt hoped to bring the two Frenchmen together and bridge the political gap between their elements. Churchill, who was close to de Gaulle, knew that events would not unfold quite as smoothly as FDR hoped. De Gaulle, a far superior political tactician than Giraud, was able to use Casablanca as a springboard to unify the French under his banner. By October of 1943, de Gaulle had consolidated his power the Free French capital in Algiers and recaptured the first territory of the French homeland with the invasion of Corsica.

In spite of his position as leader of the Free French, de Gaulle was left out of the planning for D-Day. President Roosevelt had directed Churchill to not provide de Gaulle with strategic details of the imminent invasion because he did not trust him to keep the information to himself. However, on June 2, 1944, Churchill disregarded FDR’s request and informed de Gaulle of the imminent invasion. De Gaulle was furious when he learned that the Allies, under the direction of FDR, intended to install a provisional Allied military government in place of the Vichy government with elections to be held at the first possible time. He demanded to know why he should “lodge his candidacy for power in France with Roosevelt” and declared that the “French government already exists.”

At 5:45 the morning of June 6, 1944, Operation Overlord, known commonly as D-Day commenced. By days end, nearly 160,000 Allied troops, including many Free French forces, had crossed the English Channel. As the invasion slowly progressed and the Germans were pushed back, de Gaulle made preparations to return to France. By June 12, the Allies held a beach-head 60 miles long and 15 miles deep. Two days later, Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French returned to his beloved homeland after four harrowing years in exile.

1944-1946: Provisional Government of Liberated France

Upon landing, de Gaulle’s first concern was the legitimization of his government on French soil. The city of Bayeux was immediately declared the temporary capital of Free France as the Allied forces continued the push to Paris. General Philippe Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division entered the outskirts of the city on August 24th and after six days of fighting—during which the resistance played a major part—Paris was liberated.

Two days into the siege, Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, entered Paris as liberator. As he paraded through the streets of Paris, de Gaulle came under sniper fire by enemy combatants. A BBC correspondent at the scene reported that “General de Gaulle walked straight ahead into what appeared to me to be a hail of fire … but he went straight ahead without hesitation, his shoulders flung back, and walked right down the center aisle, even while the bullets were pouring about him.” After the failed assassination, de Gaulle addressed the citizens of Paris. He declared that Paris was “liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the assistance of the armies of France, with the support and assistance of the whole of France.”

With de Gaulle’s return to Paris, Washington and London agreed to accept the Free French as the official governing body of France. The following day General Eisenhower gave his de facto blessing with a visit to the General in Paris.

The Provisional Government of the French Republic was formed on 10 September 1944. It was not until October of 1945 that elections were held for a new Constituent Assembly. Once in place the assembly unanimously elected Charles de Gaulle to lead the new government. Barely two months after his election, de Gaulle abruptly resigned. The move was a bold and ultimately foolish political ploy. De Gaulle had hoped that as a war hero, he would be soon brought back as a more powerful executive by the French people. However, that did not turn out to be the case. With the war finally over, the initial period of crisis had passed and de Gaulle suddenly did not seem so indispensable. After monopolizing French politics since 1940, Charles de Gaulle suddenly dropped out of sight. He returned to his home at Colombey to write his war memoirs.

The Politics of Grandeur

For the next twelve years de Gaulle remain on the side lines of French politics. During this time, Paris struggled to retain control over its far-flung empire as one by one its colonial possessions across the global declared and won independence. Then, in 1958, the Fourth Republic collapsed under the weight of the post war instability.

The breaking point was the Algerian War, which by May of 1958, threatened to spill into metropolitan areas of France. Many in France viewed the Algerian crisis to be the direct result of ineffective leadership in Paris. De Gaulle was believed to be the only public figure capable of rallying the nation and giving direction to the French government.

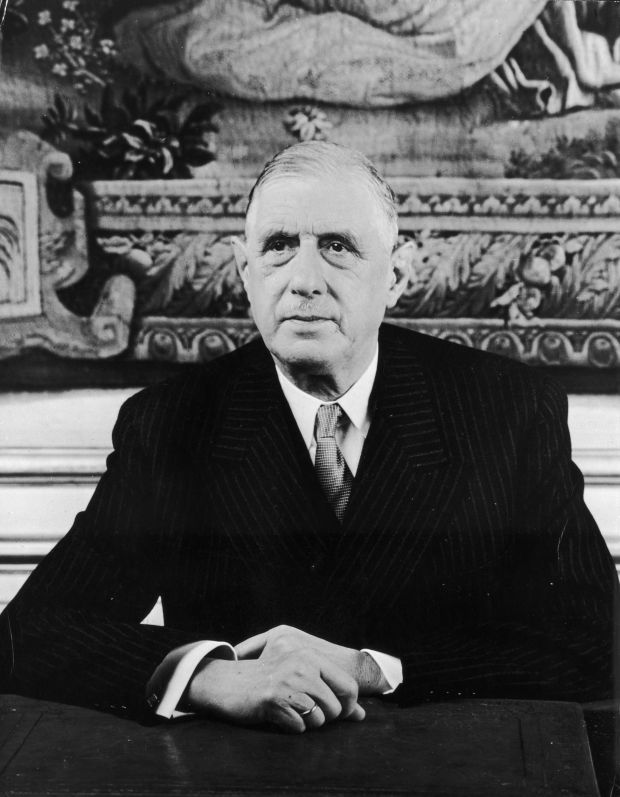

Thus, in 1958 de Gaulle once again took center stage in French politics. Immediately, he set out to quell the Algerian crisis by unify and strengthening France just as he had during the desperate war years of the 1940’s. After neutralizing the conflict in Algeria, de Gaulle turned his attention to economy re-development, and the development of a strong, independent presence on the international stage. This two-pronged policy was referred to as the Politics of Grandeur.

During his presidency, de Gaulle maintained the same intransigent attitude that he had displayed throughout the war years. Despite his hard-nosed approach, de Gaulle managed to unify his country and lead France through Thirty Glorious Years of economic growth.

Finally, in 1969 de Gaulle retired from politics for the last time. He returned, once again, to his home at the country estate of La Boisserie were he continued to write his memoirs.

On November 9, 1970, Charles de Gaulle died at his home two weeks before his 80th birthday. De Gaulle’s death was broadcast on television 18 hours later. The announcement simply said “General de Gaulle is dead. France is a widow.”

For nearly 60 years, de Gaulle had actively worked to restore a sense of France’s ancient glory and grandeur. When his superiors abandoned their belief in the sovereignty of France, de Gaulle had remained steadfast in his devotion to county and countrymen. Through sheer force of will, de Gaulle managed to unify the scattered remnants of his beloved country and emerging victorious from the crucible of exile. By 1944, de Gaulle had become more then a soldier, he had become synonymous with France itself.